HISTORICAL GARDENS

Agostino Chigi’s Renaissance Garden

La villa suburbana del banchiere senese Agostino Chigi, detto il “Magnifico” (1466-1520), esempio significativo della cultura rinascimentale, corrispose al gusto del proprietario di possedere una dimora lontana dai clamori dell’Urbe, immersa nel verde.

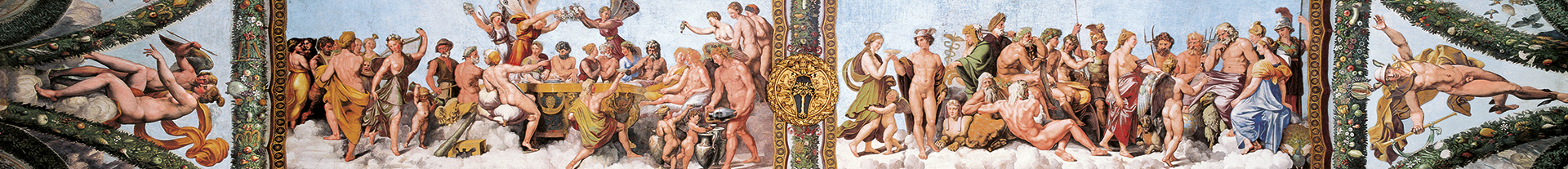

Nel Cinquecento la Villa era circondata da un meraviglioso viridarium la cui composizione si collegava armoniosamente con le stesse forme architettoniche della villa attraverso i due avancorpi laterali della facciata del fabbricato, con le festose decorazioni floreali della Loggia di Amore e Psiche, opera di Giovanni da Udine.

Le straordinarie rappresentazioni di piante del Nuovo Mondo, quali il mais, gli zucchini, la zucca maggiore e quella muschiata, il fagiolo comune, piante officinali, piante da frutto, ma anche specie ornamentali ed esotiche furono realizzate con l’intento di stupire e di suscitare l’ammirazione del visitatore e per mostrare agli ospiti, dignitari della corte pontificia, e allo stesso pontefice, la magnificenza e la raffinatezza del proprietario Chigi.

The Secret Garden and the Formal Garden

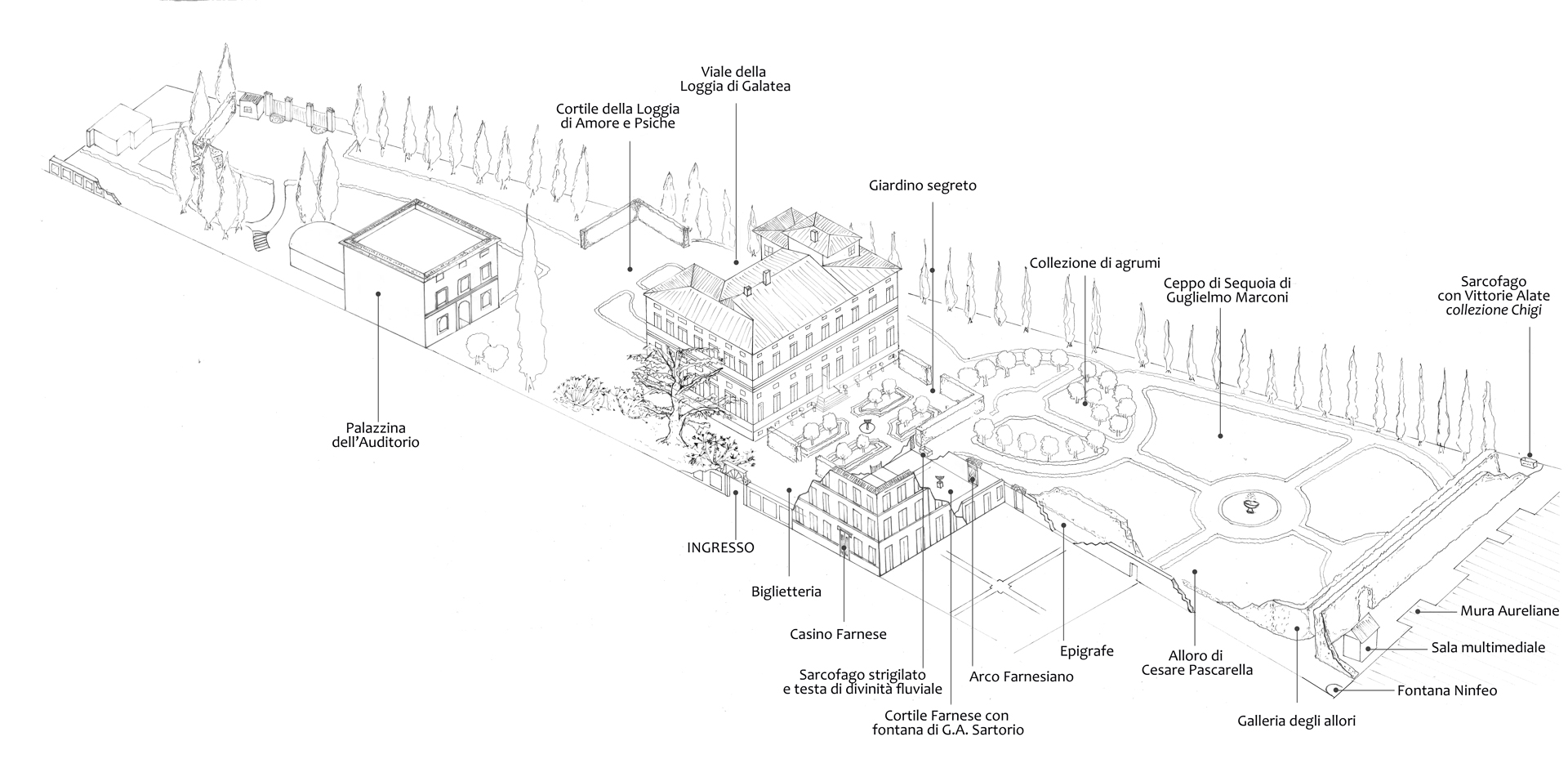

Today only a small strip of the northern part of the garden remains, while at the back of the Villa (south side, where the entrance is now) one accesses the “secret garden” inspired by the sixteenth-century hortus conclusus, separated, by means of a high hedge, from the “formal garden“.

The latter extends southward to a section of the Aurelian Walls which constitutes one of the few remains of the wall circuit that stood on the right bank of the Tiber, whose side toward the river was lost in the late nineteenth-century renovation works.

Between restoration, botany and archaeological finds

After a careful restoration intervention, tree specimens have found their home according to the eighteenth-nineteenth century arrangement: pines and some cypresses, the laurel grove – which constitutes, perhaps, the most ancient pre-existence – useful and ornamental species (roses, quinces, medlars, farnesiana acacia, Constantinople acacia, collection citrus fruits, cherry trees, holm oaks, antique camellias), some shrub species mentioned in archival documents, such as Myrtus communis, Cornus mas, Berberis, as well as perennial herbaceous plants and bulbs such as Viola odorata in ancient varieties, Lilium, Hyacinthus and Iris that compose the varied and colorful border along the ancient Farnesian wall.

A small collection of archaeological artifacts, sarcophagi, capitals and statues used as decorative elements, contributes to testifying to the ancient opulence of an environment rich in surprising pleasantness, in the heart of Trastevere.