THE HISTORIC GARDENS

The suburban villa of the Sienese banker Agostino Chigi, known as ‘il Magnifico’ (1466-1520), is a significant example of Renaissance culture and reflected the owner’s desire to have a residence far from the hustle and bustle of the city, surrounded by greenery.

In the 16th century, the villa was surrounded by a marvellous viridarium, whose composition harmoniously linked with the architectural forms of the villa itself through the two side wings of the building’s façade, with the festive floral decorations of the Loggia of Love and Psyche, the work of Giovanni da Udine.

The extraordinary representations of plants from the New World, such as corn, courgettes, pumpkins and musk melons, common beans, medicinal plants, fruit plants, as well as ornamental and exotic species, were created with the intention of astonishing and arousing the admiration of visitors and showing guests, dignitaries of the papal court, and the pontiff himself, the magnificence and refinement of the owner, Chigi.

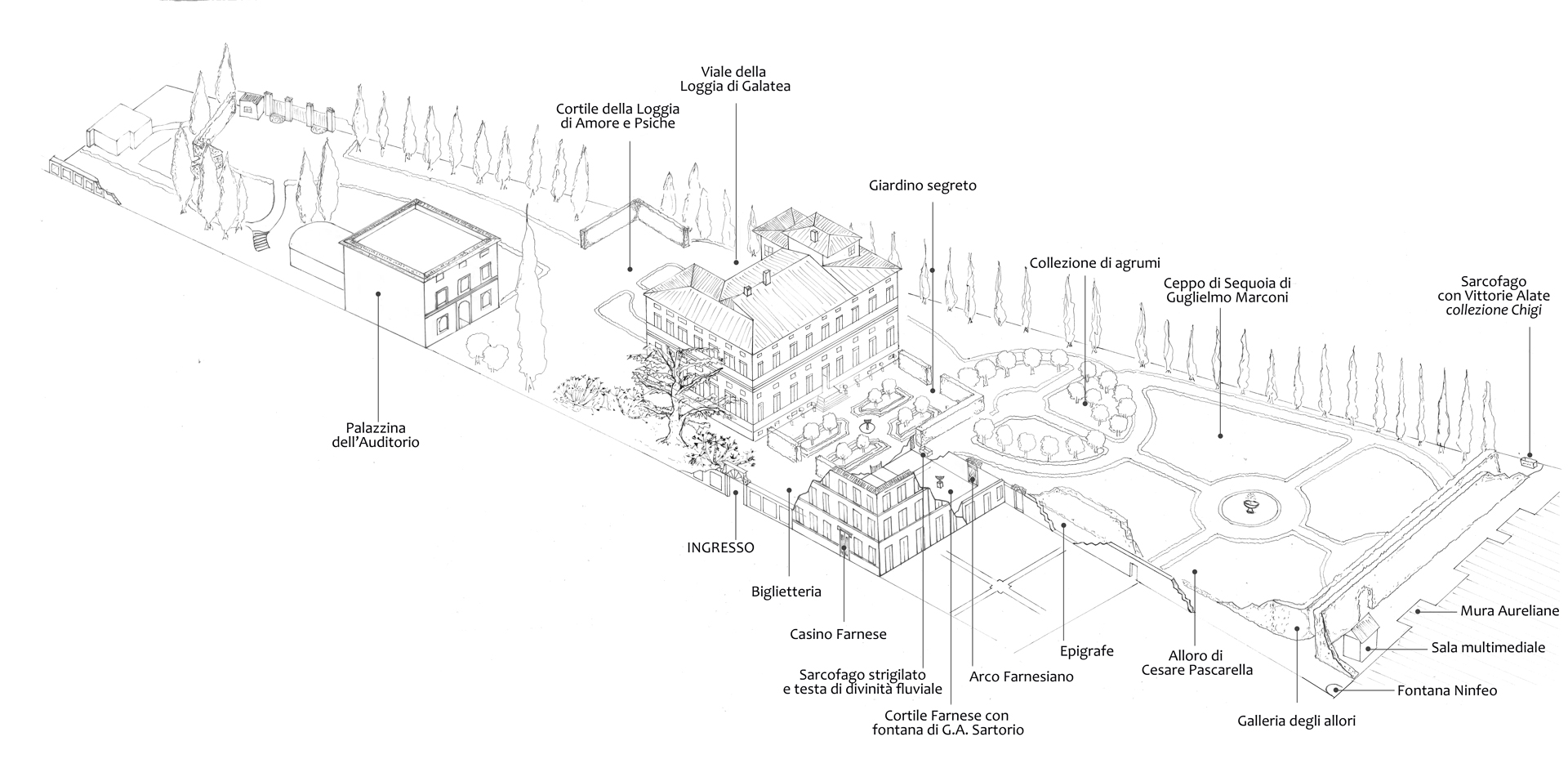

Today, only a small section of the northern part of the garden remains, while at the rear of the Villa (on the south side, where the entrance is now located) there is access to the “secret garden”, inspired by the 16th-century hortus conclusus, separated from the “formal garden” by a high hedge.

The latter extends southwards to a section of the Aurelian Walls, one of the few remaining parts of the city walls that stood on the right bank of the Tiber, the side facing the river having been lost during renovation work at the end of the 19th century.

After careful restoration work, trees have been replanted according to the 19th- and 20th-century layout: pines and some cypresses, the laurel grove – which is perhaps the oldest existing feature – useful and ornamental species (roses, peaches, medlars, Farnesiana acacia, Constantinople acacia, collectible citrus fruits, cherry trees, holm oaks, ancient camellias), some shrub species mentioned in archival documents, such as Myrtus communis, Cornus mas, Berberis, as well as perennial herbaceous plants and bulbous plants such as Viola odorata in ancient varieties, Lilium, Hyacinthus and Iris, which make up the varied and colourful strip along the ancient Farnese wall.

A small collection of archaeological finds, sarcophagi, capitals and statues used as decorative elements, bears witness to the ancient opulence of a surprisingly pleasant environment in the heart of Trastevere.