The Hall of the Frieze

The room, used as a waiting room for guests but also for important ceremonies such as the reading of the banker’s will, is named after the frieze that runs along the top of the walls

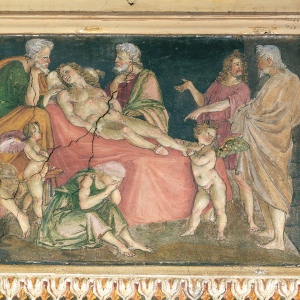

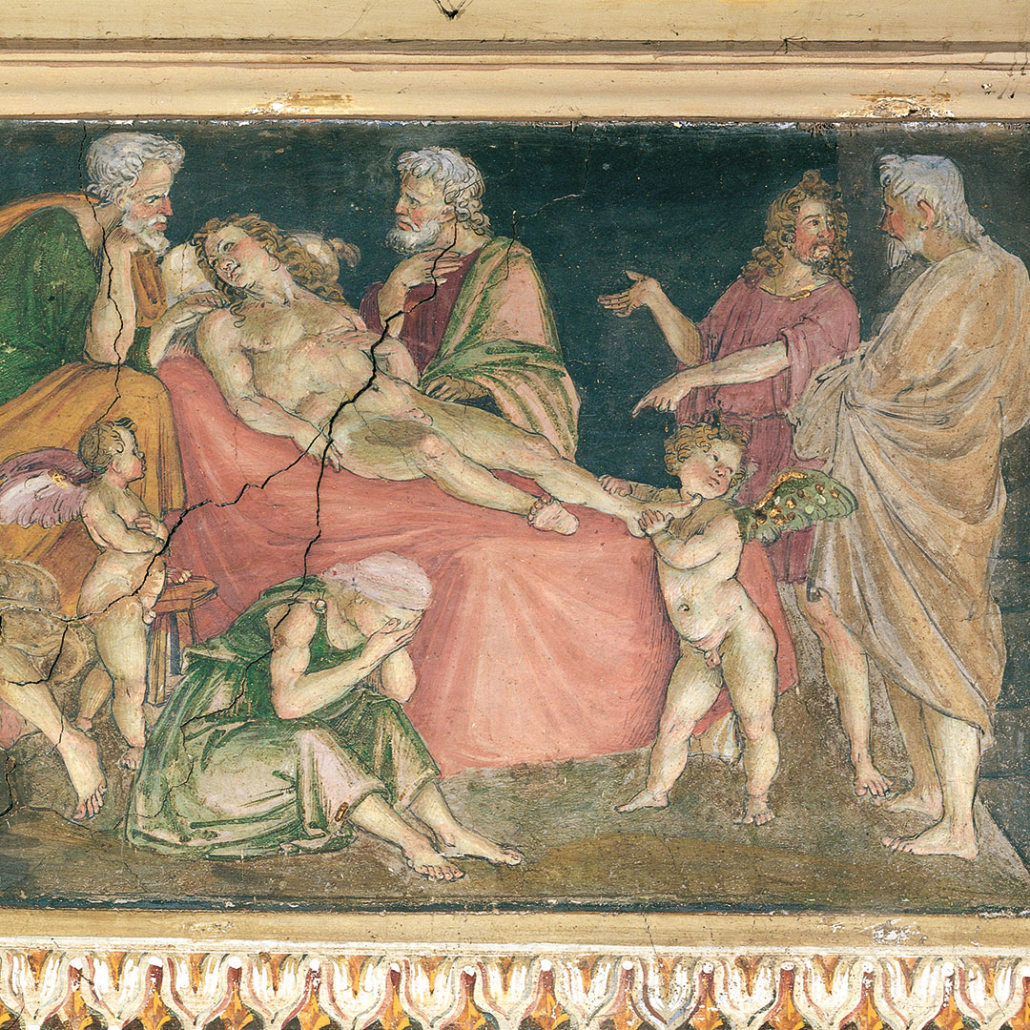

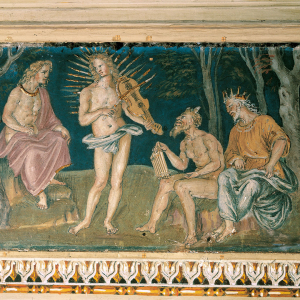

It was created by Baldassarre Peruzzi, who frescoed it around 1508, depicting, with clear allegorical allusions to the virtues of the client, the twelve labours of Hercules on the north side and partly on the east side, and other exploits of the hero, as well as various mythological episodes (the rape of Europa, Apollo and Marsyas, Orpheus and Eurydice…) that follow one another without interruption.

In the 19th century, the Villa Farnesina was one of the most visited places in Rome by scholars from all over Europe. In 1861, Francesco II of Bourbon commissioned the architect Antonio Sarti and the painter Tommaso Minardi to draw up two reports on the state of the Farnesina building and the state of the frescoes respectively. Following this rather alarming assessment, between 1863 and 1866 the Duke of Ripalda promoted a series of renovation works under the direction of architects Antonio Cipolla and Antonio Sarti.

The architect Antonio Cipolla (1820-1874) was the trusted architect of the Bourbons and, in this capacity, restored both Palazzo Farnese and Villa Farnesina. Faced with the need to respect the character of two of the most important examples of 16th-century architecture, he chose to proceed according to the dual approach of restoring the great pictorial cycles and transforming anonymous, uncharacteristic rooms into places worthy of a court, but in harmony with the 16th- and 17th-century tradition.

The atmosphere in Rome at that time was fully in tune with such a cultural attitude, as evidenced, among other initiatives, by the completion of Raphael’s Loggias and the restoration of early Christian churches promoted by Pius IX, culminating in the grandiose undertaking of San Paolo Fuori Le Mura. .

The choice of faux curtain decorations commissioned by the Duke of Ripalda appears to perpetuate the use of wallpaper as a choice that influences the furnishings, perception, use and even the life of the palace rooms.

In the hall, as in the Loggia di Galatea (where the Duke of Ripalda’s mosaic coat of arms stands out in the centre), there is a floor made of terrazzo or “Venetian terrazzo”. This is an ancient technique, widespread in Genoa and Venice as early as the Renaissance, which was then exported to central Italy and abroad to decorate the interiors of noble palaces.